Exclusive: Top Infectious Disease Doctor Sits Down With The Willistonian

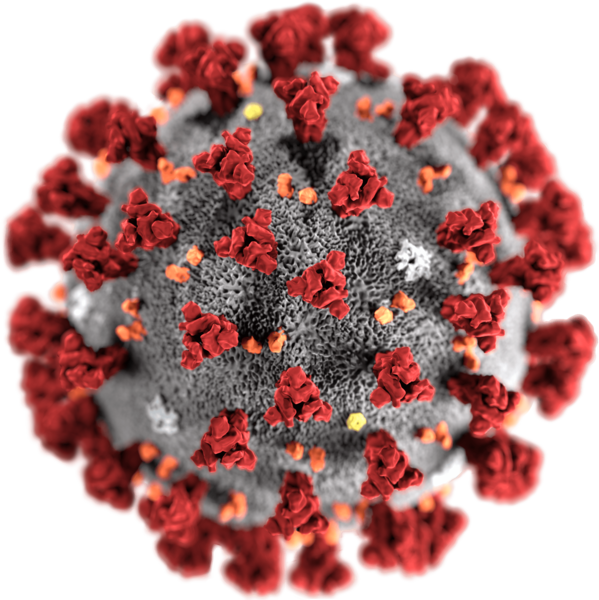

Render of 2019-nCoV virion

While Health and Wellness may currently be giving hundreds of students flu shots, administering the upcoming coronavirus vaccine could be their next task.

Pfizer’s coronavirus vaccine emerged as the frontrunner of potential vaccines against SARS-CoV-2, demonstrating 90% efficacy after their phase three trial, according to Pfizer. The vaccine was first administered to the public on December 14, 2020. Now that millions around the world have received at least their first of two doses of the vaccine, Williston will soon have to decide how, when, and if they want students vaccinated.

Dr. Donna Fisher, Chief of Pediatric Infectious Diseases at Baystate Medical Center for over 20 years, spoke to The Willistonian about how soon a vaccine could be made available to students.

[Editor’s Note: Fisher spoke with The Willistonian before the vaccine had officially been released.]

“Plans for distribution of a vaccine [are to] healthcare workers, essential workers (post office, delivery people, fire, police, EMT),” Dr. Fisher wrote in an email to The Willistonian. “Distribution plans are done by ‘working groups’ [from] the state’s public health departments who will get shipments of federally purchased vaccine supplies. Those teams are tasked with making a decision about equity,” she emphasized. “Lots of dilemmas with that, as you might imagine.”

According to Dr. Fisher, the vaccine will probably not be made available to high school students for “a while.”

“Children 12 [years] and older are just now being enrolled into these vaccine trials, so we don’t know when school children will be likely to get [the] vaccine,” she wrote. “Schools don’t enter into plans right now, but I’m sure it will not be made a ‘mandatory’ vaccine anytime soon.”

Christopher Pelliccia, a chemistry teacher at Williston, told The Willistonian that he believes state funding will play a role in proper distribution.

“As I see it, there are two main issues: manufacturing and distribution,” he said. “State-level distribution has not been properly funded by the current administration, so I worry about how complete vaccination efforts will be.”

Alluded to by Dr. Fisher, Pelliccia is also concerned about the social implications of vaccine distribution.

“On a practical level, reaching very rural or underfunded communities will be difficult. Vaccine mistrust and Covid skepticism in this country will also make reaching herd immunity very difficult,” he said.

Amy Lehane, a nurse at Health and Wellness, is unsure if Williston will be responsible for distributing Pfizer’s vaccine, as there may be some technical issues.

“I read an article recently that said the Pfizer vaccine has to be stored at -70 to -80 degrees Celsius. Even some large medical facilities may not have storage at that temperature, and we don’t currently have such storage at Williston,” she noted. “Although Pfizer can ship it on dry ice, there are still some logistics to work out.”

The Pzifer vaccine uses mRNA technology, explained by Paula Cannon, Associate Professor of Microbiology at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine, in an interview with Denise Chow of NBC News.

“When one particular gene needs to do its work, it makes a copy of itself, which is called messenger RNA. If DNA is the big instruction manual for the cell, then messenger RNA is like when you photocopy just one page that you need and take that into your workshop,” Cannon said.

In terms of how the vaccine works, Dr. Fisher gave The Willistonian some insight on the mRNA in action.

“[The Pfizer vaccine] work[s] by sending a piece of RNA that codes for a sticky, spiky outer protein of the virus into the vaccine recipients white cells, and then the machinery is turned on to actually manufacture the protein stick/spike.” She continued, “Then, the recipient’s other immune cells recognize this protein stick as “foreign” and the person makes “protective” antibodies. It’s very cool.”

In the same NBC News article by Chow, Dr. Carlos del Rio, Executive Associate Dean of the Emory University School of Medicine, spoke about how the vaccine is the first of its kind.

“There were a lot of people who were skeptical that an mRNA vaccine would work. Scientifically, it makes sense, but there’s no mRNA vaccine out there that has been approved yet,” he said.

Among the list of guidelines posed by Williston in the Community Health Compact signed by students in August, getting the potential mRNA vaccine was not explicitly stated, making it unclear if students will be asked to get the vaccine before the end of the school year.

While the Williston Community Health Compact does not directly address a potential vaccine against the Coronavirus, it does acknowledge the uncertainty surrounding the virus and that students must adhere to any additional requirements posed by Williston.

The Compact states, “I [the student] agree to abide by any new expectations, rules, and guidelines issued by Williston in order to remain a member of the community.”

Essentially, this statement serves as the “Necessary and Proper Clause” of the Williston Community Health Compact. Found in Article I, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution the “Necessary and Proper Clause” gives Congress (or in Williston’s case, the Deans’ office) the power “To make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing Powers.” Potentially, Williston could expand the contract to require the vaccine.

On the student end, junior Sarah Markey is prepared to get the vaccine as soon as it is ready.

“I think the Coronavirus vaccine should be distributed to minorities and the groups that are the highest risk, but as soon as it’s released to the public, students should also get it.”

Abby Schulkind, a senior, joked about getting the vaccine as long as it is safe.

“I’ll get it,” she laughed. “But I’ll wait a week first to see if anyone grows an extra arm.”

Anna is from Granby, Massachusetts. She enjoys watchign Grey's Anatomy, running, and riding horses. She has watched all seasons of Grey's Anatomy.